NB No spoilers for Singularity, ending spoilers for Jurassic Park: The Game.

I'm fascinated by the psychological and creative theory behind interactive narrative. It scares, confuses and enthrals me. Much as there's more and more writing on such topics, I still don't feel like we always understand just what we're doing to the player when we give him a decision to make. I still hold that the logical solution is to tend towards more procedural (albeit less narratively detailed) content: the more dynamic a game world is the more decisions within that world function like real ones (ie a question of knowledge, odds and cause and effect); however more often than not I find myself working with more scripted experiences which send the player off to either (a) or (b).

Singularity

Where this approach often seems most indelicate is in games with multiple endings. Take Singularity. Without spoiling anything significant, the game's entirely linear, encouraging the player to let the fiction take over: these are the good guys, these are the bad guys, go fight for what's right. At the end, though, you're given a choice: side with the good guys, or the bad guys. For me it renders the rest of the experience completely disingenuous: if this was always an option, why have I only just heard about it? If you wanted me to actually engage my brain and consider the ethical situation I'm presented with, why force me to fight for the good guys the whole way through?

I'm sure we can guess why this decision point is in here. In fact the presentation of the endings tells the tale for us: the good ending is a lavishly presented cut scene; the other two just have naff voice overs. A last minute decision that sounded good on paper, then: of course the player wants to choose who to side with! Of course branching endings are better than straight ones!

It's understandable, because surely more player choice can't be a bad thing? I'm going to argue that, in fact, as far as endings go it can be just that.

Endings in Games vs Endings Everywhere Else

I was considering a scenario for an unannounced project the other day. There was an obvious opportunity for the player to make a decision at the end of the game (let's say he's got a bad guy at gunpoint). It's a secondary character who we can kill off or let live, and we can let that decision affect one or two minor story elements later on. But here's the thing: what decision are we asking the player to make here? Is it between revenge and mercy? Is it between good and evil? Is it between practicality and empathy?

The truth is that in real life (which is what we tend to be modelling with decisions in games) it's all of these things, but the only thing that defines the outcome of the decision once made is raw cause and effect. The more we know about the situation the more able we are to predict its outcome; and when it swings unpredictably (let's say I kill the baddie to be on the safe side, but his brother comes and takes revenge) we accept it as either an oversight on our part, or an unfortunate roll of the dice. This is exactly how such decisions play out in an entirely procedural environment like Spelunky.

But how does this sort of decision point work in the game? Well, for one thing we're going to pre-define the outcome based on what we consider realistic or, perhaps more likely, on what the story and gameplay demand. We're also incapable of understanding what your reasons were for that decision (unless it's a very particular one), which largely negates any useful story consequences we can impose.

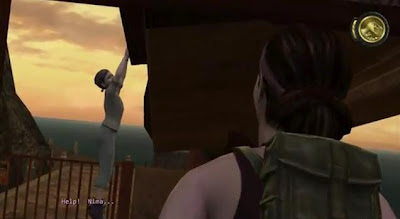

Jurassic Park

Let's take a further example from Jurassic Park: The Game. Major plot spoilers here, but honestly the story's not up to much anyway so don't fret. At the end of the game one of your characters has a decision to make (just like Singularity, it's the only one in the game): save the valuable dino DNA, or save the little girl. I accidentally selected 'Save Little Girl', and I got the happily ever after ending where everyone escapes together and - incredibly - they also happen across a great big bag of gold. Now, the way this is presented suggests going after the DNA was a valid alternative, so I went back and tried again. Turns out when you go after the DNA the character in question winds up getting eaten, and the little girl escapes anyway.

It's obvious enough what Telltale are doing here. We're not being asked to make a practical decision (since both options seem equally risky), we're being asked to make a moral one. The message: be good and your rewards will come; be an arsehole and you'll get digested by a T-Rex. But what if I went after the DNA because I thought the girl was already done for? What if I just put higher ethical value in scientific progress as a whole than in individual human life? What if I panicked and hit the wrong button? Because it's not clear this is a soley ethical dilemma we're confusing this decision; with so many unpredictable factors (the author's hand, the artificial cause and effect of gameplay, the implied freedom of choice) the decision winds up doing very little.

Games vs Films

I don't think there's been a single game with branching endings (since, at least, the internet age) where I didn't immediately go online and see what I missed out on, and I wonder whether that's telling of how unsuccessful games often are in selling to the player that the ending they got is their ending; that it's appropriate to their story. But it also raises some interesting comparisons with film that might shed some light. The entirety of film is 'tainted' by the author's hand. Sure, things usually roll out with a semblance of plausible cause and effect, but unlike games there's nothing in here that's down to chance. There is one route through this narrative, the intended route, and when a character reaches a decision point it's usually made abundantly clear what the alternative was, and why he didn't choose it. The question of 'What if?' is either answered implicitly, or unimportant.

When I dig out the alternate ending to Singularity or Jurassic Park it certainly decreases my identification with the ending I naturally received. The illusion that I had much ownership of this tale is shattered, and often there's little that occurs that isn't predictable (and yet, of course, were it less so we'd be complaining that it wasn't appropriate for a bunch of other reasons). These endings tend to be so run of the mill: we're making a cyber punk shooter, there are three factions in the game, of course you get to choose which one you like at the end!

However, viewing what might have happened can also be illuminating, and it's an option unique to our medium. The good ending in Jurassic Park is an awful lot more meaningful (though sadly no more interesting) once I know what the alternative was. When we consider the difference between the illusion of freedom and true freedom, knowing what your other options were at least confirms that you had freedom of a meaningful sort.

Conclusions

So back on topic, what did I do in my execution scenario? Well, I thought about playing the odds. Make it clear to the player what possible ramifications exist (ie the vengeful brother), and then assign it a probability. For 75% of players it's a risk worth taking; the rest get unlucky. In the end I decided there were too many factors at work. I'd rather provide a linear experience that's at least true to itself (whose drama plays out in a meaningful way) than provide the player a decision point just because I can, and risk him being alienated because I haven't properly accounted for his motivation.

There's a danger, in this piece, that I'm just complaining about all the options available to a narrative designer, without proposing solutions. Given my theoretical leaning towards procedural play there's no doubt some truth to that, but I'm not happy leaving it there.

At Southbank, I always push my story design students to ensure any branching they consider is appropriate to the player. There's no point giving him ownership of the story if it doesn't branch in a way that's more meaningful for him than it might be for differently disposed players, and that principle carries over to this discussion. Singularity: there's nothing wrong with a tightly crafted linear experience, so just bite the bullet.

The game I'm working on does have multiple endings. It's a risk. But we're conscious of that fact, and we're working hard from the get go to ensure it's based on meaningful player decisions. Perhaps more importantly we're not throwing in decisions just for the sake of it. When a player comes into our game I want him to know what his options are, and what they're not; and while I don't want him to see the ending coming, I want it to feel appropriate nonetheless.

We'll find out whether we succeed early next year.

I'm fascinated by the psychological and creative theory behind interactive narrative. It scares, confuses and enthrals me. Much as there's more and more writing on such topics, I still don't feel like we always understand just what we're doing to the player when we give him a decision to make. I still hold that the logical solution is to tend towards more procedural (albeit less narratively detailed) content: the more dynamic a game world is the more decisions within that world function like real ones (ie a question of knowledge, odds and cause and effect); however more often than not I find myself working with more scripted experiences which send the player off to either (a) or (b).

Singularity

Where this approach often seems most indelicate is in games with multiple endings. Take Singularity. Without spoiling anything significant, the game's entirely linear, encouraging the player to let the fiction take over: these are the good guys, these are the bad guys, go fight for what's right. At the end, though, you're given a choice: side with the good guys, or the bad guys. For me it renders the rest of the experience completely disingenuous: if this was always an option, why have I only just heard about it? If you wanted me to actually engage my brain and consider the ethical situation I'm presented with, why force me to fight for the good guys the whole way through?

I'm sure we can guess why this decision point is in here. In fact the presentation of the endings tells the tale for us: the good ending is a lavishly presented cut scene; the other two just have naff voice overs. A last minute decision that sounded good on paper, then: of course the player wants to choose who to side with! Of course branching endings are better than straight ones!

It's understandable, because surely more player choice can't be a bad thing? I'm going to argue that, in fact, as far as endings go it can be just that.

Endings in Games vs Endings Everywhere Else

I was considering a scenario for an unannounced project the other day. There was an obvious opportunity for the player to make a decision at the end of the game (let's say he's got a bad guy at gunpoint). It's a secondary character who we can kill off or let live, and we can let that decision affect one or two minor story elements later on. But here's the thing: what decision are we asking the player to make here? Is it between revenge and mercy? Is it between good and evil? Is it between practicality and empathy?

The truth is that in real life (which is what we tend to be modelling with decisions in games) it's all of these things, but the only thing that defines the outcome of the decision once made is raw cause and effect. The more we know about the situation the more able we are to predict its outcome; and when it swings unpredictably (let's say I kill the baddie to be on the safe side, but his brother comes and takes revenge) we accept it as either an oversight on our part, or an unfortunate roll of the dice. This is exactly how such decisions play out in an entirely procedural environment like Spelunky.

But how does this sort of decision point work in the game? Well, for one thing we're going to pre-define the outcome based on what we consider realistic or, perhaps more likely, on what the story and gameplay demand. We're also incapable of understanding what your reasons were for that decision (unless it's a very particular one), which largely negates any useful story consequences we can impose.

Jurassic Park

Let's take a further example from Jurassic Park: The Game. Major plot spoilers here, but honestly the story's not up to much anyway so don't fret. At the end of the game one of your characters has a decision to make (just like Singularity, it's the only one in the game): save the valuable dino DNA, or save the little girl. I accidentally selected 'Save Little Girl', and I got the happily ever after ending where everyone escapes together and - incredibly - they also happen across a great big bag of gold. Now, the way this is presented suggests going after the DNA was a valid alternative, so I went back and tried again. Turns out when you go after the DNA the character in question winds up getting eaten, and the little girl escapes anyway.

It's obvious enough what Telltale are doing here. We're not being asked to make a practical decision (since both options seem equally risky), we're being asked to make a moral one. The message: be good and your rewards will come; be an arsehole and you'll get digested by a T-Rex. But what if I went after the DNA because I thought the girl was already done for? What if I just put higher ethical value in scientific progress as a whole than in individual human life? What if I panicked and hit the wrong button? Because it's not clear this is a soley ethical dilemma we're confusing this decision; with so many unpredictable factors (the author's hand, the artificial cause and effect of gameplay, the implied freedom of choice) the decision winds up doing very little.

Games vs Films

I don't think there's been a single game with branching endings (since, at least, the internet age) where I didn't immediately go online and see what I missed out on, and I wonder whether that's telling of how unsuccessful games often are in selling to the player that the ending they got is their ending; that it's appropriate to their story. But it also raises some interesting comparisons with film that might shed some light. The entirety of film is 'tainted' by the author's hand. Sure, things usually roll out with a semblance of plausible cause and effect, but unlike games there's nothing in here that's down to chance. There is one route through this narrative, the intended route, and when a character reaches a decision point it's usually made abundantly clear what the alternative was, and why he didn't choose it. The question of 'What if?' is either answered implicitly, or unimportant.

When I dig out the alternate ending to Singularity or Jurassic Park it certainly decreases my identification with the ending I naturally received. The illusion that I had much ownership of this tale is shattered, and often there's little that occurs that isn't predictable (and yet, of course, were it less so we'd be complaining that it wasn't appropriate for a bunch of other reasons). These endings tend to be so run of the mill: we're making a cyber punk shooter, there are three factions in the game, of course you get to choose which one you like at the end!

However, viewing what might have happened can also be illuminating, and it's an option unique to our medium. The good ending in Jurassic Park is an awful lot more meaningful (though sadly no more interesting) once I know what the alternative was. When we consider the difference between the illusion of freedom and true freedom, knowing what your other options were at least confirms that you had freedom of a meaningful sort.

Conclusions

So back on topic, what did I do in my execution scenario? Well, I thought about playing the odds. Make it clear to the player what possible ramifications exist (ie the vengeful brother), and then assign it a probability. For 75% of players it's a risk worth taking; the rest get unlucky. In the end I decided there were too many factors at work. I'd rather provide a linear experience that's at least true to itself (whose drama plays out in a meaningful way) than provide the player a decision point just because I can, and risk him being alienated because I haven't properly accounted for his motivation.

There's a danger, in this piece, that I'm just complaining about all the options available to a narrative designer, without proposing solutions. Given my theoretical leaning towards procedural play there's no doubt some truth to that, but I'm not happy leaving it there.

At Southbank, I always push my story design students to ensure any branching they consider is appropriate to the player. There's no point giving him ownership of the story if it doesn't branch in a way that's more meaningful for him than it might be for differently disposed players, and that principle carries over to this discussion. Singularity: there's nothing wrong with a tightly crafted linear experience, so just bite the bullet.

The game I'm working on does have multiple endings. It's a risk. But we're conscious of that fact, and we're working hard from the get go to ensure it's based on meaningful player decisions. Perhaps more importantly we're not throwing in decisions just for the sake of it. When a player comes into our game I want him to know what his options are, and what they're not; and while I don't want him to see the ending coming, I want it to feel appropriate nonetheless.

We'll find out whether we succeed early next year.

This post: worth it just for the Planescape header.

ReplyDeleteWhat were your experiences with these games?

Not having played either of these I can only go on your descriptions, but I know the feeling. Deus Ex magnificently undermines itself at the end by letting you choose any ending.

ReplyDeleteIn Jurassic Park the choice can readily be made by asking 'what would a character in a Jurassic Park movie do?' Going for the dino-greed option would clearly condemn you to death at the tiny hands of the terrifying t-rex. You could perhaps console yourself that you were a complex character, with good intentions that lead you astray, but Hollywood cannot be argued with. You Were Deluding Yourself and your death shall be A Lesson To Others.

As for the multiple endings I liked the inversion in Dragon Age: Origins (in theory, if not execution) - have multiple starts instead.

Mass Effect also nuanced this slightly by giving you a series of unclear either/or decisions instead of just the one biggie at the end.

Well, when I read the first paragraph I thought "Oh damn, I haven't played either of the 2 games". Then it dawned on me: I _had_ actually played singularity and forgotten all about it!

ReplyDeleteThere's a good reason for it though: I played it completely like a mindless shooter, skipped all cutscenes that could be skipped, and rushed to the end. I think I tried both endings but wasn't impressed with either ending. Apart from the time-rewind-of-a-certain-area gimmick (which was forced in the game as a critical element in order to progress at some points), the game brought nothing new to the table regardless of its nice presentation and execution. So I forgot about it!

I'm totally sure I've never player Jurassic Park though so I can't comment about it.

Your article reminded me of the Silent Hill games. Especially 2 and 3 have multiple endings depending on how you actually play the game. I read a very comprehensive tutorial that says that you get to an ending only if you don't heal your character frequently and you let him go on with low health - that way he gets sort of emo and suicidal (iirc). I don't have the strength to replay a game, let alone replay it 5 times to see if there are any subtle changes in the story flow depending on how you play it, but the idea does have lots of potential.

I'm trying to remember more games that I played and actually thought about which ending to choose. There was Amnesia: the dark descent (one morally satisfying ending, one of betrayal and one that was undefined - afaik), and I can't think of anything else right now :) - if I do I'll get back here and write again.

In a short story by (I think) Poul Anderson, a character overcomes the pain of a toe amputation by eagerly anticipating sex with a second character. 'What would have happened if I hadn't balled Flo after?' he wonders. 'Would my toe have hurt retroactively?' (It's a whole 60s transcendence thing.)

ReplyDeleteI think the emotional fulcrum in interactive narrative is the moment of choice, not the reaction to the consequence. If the choice feels important then it's fine for the consequence to be predictable. It's like a twist ending in a film: a bad one can easily damn a film you liked, but it's rare for a good twist ending to save a bad film. The choice is the part that belongs to the player. The consequence is just the bit that we need to provide so the player's toe, as it were, doesn't hurt retroactively.

I'm exaggerating, of course, and sometimes an unexpected consequence is a useful effect - especially when you can reccover from it - but I very much sympathise with your general suspicion of sharp left turns in endings.

@CdrJameson

ReplyDeleteI do think there's a crucial angle here that I've left out: precisely that 'what would a Jurassic Park character do?' thing. Essentially: the way in which the story branches after the decision point (even if it's in a way that feels unfair or unrealistic) is precisely the way in which the designer establishes the message of the game. Sadly it's not always clear when we're being put in situation whose cause and effect is controlled by dramatic necessity (as in Jurassic Park), and when it's controlled by some approximation of reality (eg when trying to persaude a character in DX).

@ggn

The only Silent Hill I played at any length was the offbeat (though not off) Silent Hill: The Room; however what fundamentally bothers me about branching based on things like item collection or health pack usage is that these rules are specific to the game they're in; they're employing a language that isn't commonly shared. In particular, I don't think it reflects anything at all interesting about the player because his use of health kits isn't some feature of his personality (surely we all use health kits in games if available?), and he's not au fait with how his actions are being interpretted.

We're doing something similar in my current project, but we're working to inform the player implicitly about what repurcussions his actions might have; and the branching is designed in such a way as to (hopefully) only reflect the things we're testing for.

@Alexis

Well put. We're way overdue that meetup! There's a writer's pint coming up on 17th in Angel...

I felt like this sentence nailed the problem: "We're also incapable of understanding what your reasons were for that decision" - you said it yourself, it's almost impossible to know what reason a player had for making a decision when there are many angles to come from to arriv at making decision, many of which might not be at first obvious.

ReplyDeleteThe other thing of interest from this piece to me was how you checked out the other endings afterwards and how this effected how you felt about the decision you made. I've thought myself about how you allow player actions to lead to consequences and how honest you need to be with following through their actions with meaningful consequences because in a linear experience a player can be none the wiser of exactly what's under the hood of the game and so why should a game designer try to react meaningfully to every player action if you can just use illusions to fudge the issue so that the player thinks the game is responding to them more than it actually does. I've wondered about player's then potentially reading up on the game later as you did and finding out the truth and then this taking away from their experience with the game retroactively, which then makes me wonder if illusion should be avoided and proper consequences to each player action should be sacred when building the game so the player will not end up feeling tricked by the game if they research into how the backend of the game was working all along. The short story Alexis referred to is interesting with that in mind.

The funny thing is that consequences alone cannot morally judge your choice; the fact that in that situation you die and in the other you don't? Nothing you can do about that.

ReplyDeleteIt's like they missed the point of fables entirely; it's not that you go "a man stole a wallet, he was impaled by a tree", but that for some reason you want to create a chain of narrative logic from one to another.

Only then do the consequences matter, when you say they are in some way necessary consequences!

If the game designer doesn't put in the work, then you can happily ignore their "moral statements" as unrelated consequences, that could go any other way except in the artificially repeating world of the game.

One thing I wish game designers would do is start building mechanics to play out those fable chains of logic, so that it's not just a->b, but a->b->c and the game will procedurally, over time, generate roughly the moral you want, unless people subvert it. This will almost inevitably become more contingent as the length of the logic chains increase, but I think part of the reason that game's moral messages have been so trite in the past is that as children we already pick up very basic causal fables, and it's only over time that the more subtle effects become clear.

Passage is an artistically great game because it deals with simple causal links that we do not discover except with age or relationships, things that we experience, in a childlike way, for the first time when reaching certain ages. But I suspect that to tell many other kinds of moral stories, we will have to move into longer chains.

Mass effect (the series as a whole, which was on my mind the moment I saw a discussion of endings!) looks like it's wound all these people up because it places it's story structure on simple causal links that operate on multiple levels/time scales, rather than the explosive complexification that directly following plot from chained choices would require.