I don't know what I could possible write here about Chris Avellone that isn't already implicit throughout the writings on this blog. Chris' work on Planescape, Van Buren and KOTOR II was instrumental in inspiring me to do what I do, and I am not the only one. Without further ado, here's what came out of a night in the pub with Chris a couple of months ago.

Planescape was one of the games that made me get into games. Is there a substantive difference in the complexity and flexibility of Planescape's narrative as compared with modern RPGs, or do we just have rose tinted glasses applied to some cleverly hidden linearity?

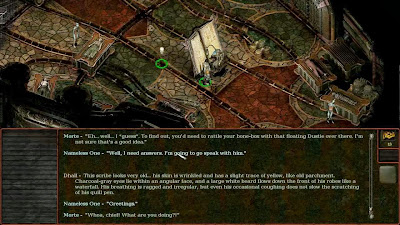

I’d say it’s the rose-tinted latter (although adding rose tints to design like this is a good skill to have, imo). Torment may have felt free, but there were some clear narrative chokepoints along the way that were necessary for the critical path. I’d argue that the context of these chokepoints could change - and not just narratively, but systematically as the flexibility in the alignment system allowed for additional opportunities. Still, there were some linear segments. We’ve tried to use this methodology in future games, however – you can get a lot more bang for your buck in terms of reactivity by tying as much reactivity as possible to the “gates” the player is going through in the game or major NPCs you’re definitely going to meet (Fhjull, Ravel, Annah, Morte, etc.).

To play devil’s (baatezu’s) advocate to the linearity point, however, we did consciously design larger game hubs that allowed the player to choose and approach quests how they wanted, which we felt was important for a role-playing game. Also, one of our design mandates was to make sure we had a lot of variation in the dialogue interactions based on the abilities and alignment shifts of the Nameless One. We wanted every conversation to have many options for any style of player – smart, strong, fast, wise, companion interjection (like with Fell, where it was critical), good, evil, lawful, chaotic, etc.

Also, the companion characters added a lot of optional content. A lot. That was a conscious design choice and went against the studio’s wishes at the time, but I felt it was important that the player be allowed to form an attachment and explore these companions in a way that allowed the player to bond and understand them on a deeper level if they wished. And in many instances (especially Dak’kon), this proved to tie into the endgame quite well and give the endgame a much different context depending on the companion interaction.

What makes a torment game what it is? Is it just what arguably every fantasy RPG should be doing: not relying on tired Tolkien tropes?

That’s a good question – I suppose it’s a mix of things: doing reversals (puritan succubus, lying angels, truthful demons, incredibly powerful rats, sympathetic undead, enslaved githzerai), defying conventions (who cares if you die - no need to reload if you don’t want to and it advances the plot and solves puzzles, you get to guide your alignment over the course of the game, bending D&D rules to serve the narrative, no elves, dwarves, minimal swords), and a personal, selfish story that doesn’t pretend to shift the focus from the player. Your personal journey’s what’s important. Sure, what happened to you as the Nameless One may mean a lot for the planes, but ultimately, it’s all referring back to you.

For me, when developing Torment I had a long list of things I didn’t care for in modern RPGs, so I re-examined all of them to figure out how to approach them differently. I feel this process (I admit I’m assuming here) worked well for Ronald Moore when he moved off Star Trek: Voyager and examined where sci-fi should go in the Battlestar: Galactica reboot. Reading his vision statement for where BSG should go was really liberating.

Planescape blew me away primarily because it had that strong character thread throughout. It wasn't about saving the world, it was about discovering things about yourself, and the nature of mankind. That's still a powerful idea mostly ignored by today's AAAs. How did you develop those ideas, and what if anything is the philosophical takeaway from Planescape for you?

It’s a selfish one, and it comes from many long years of Gamemastering: players are selfish. They want to shine. They want to stand out, be special, and be recognized for it. One of the things I detested about a number of RPGs at the time was that these RPGs seemed driven to make you care about some crappy nation or nebulous figure to be saved, to force some kind of relationship and worse, try to force you to care about that relationship, when what a game designer should consider is simply focusing on the player’s own desire to play the game themselves. Make it solely about them. It’s fine if EVERYTHING in the game revolves around them. In fact, make that their story, their narrative journey, and you’ll likely have a much better game for it by stripping away all the bullshit.

What weren't you happy with in Planescape, and how is that influencing work on Tides of Numenera? And how do you say 'Numenera'?

It’s NEW-MEN-ERA. I could telepathically feel Monte Cook wincing every time I mispronounced it (which was a bonus), and I actually mispronounced it in one of the best takes of the Torment endorsement video. ;)

I thought the combat in Planescape was poor, there weren’t enough Planes to explore (we wanted more), and it could have used more fun dungeon and adventure locations as well. That said, Planescape taught me that you don’t always need to one-up the companion roster, one-up the inventory list, spell list, or any of the systems you’re being compared to as long as you set up the narrative and the world context to explain why and you’ll likely have a much better game for it.

Was I worried about the number of companions in Torment vs. Baldur’s Gate? Yep. Was I worried about the lack of inventory items and weapons you could equip? Yep. Was I worried about the character creation and lack of class options for the main character? Yep. But in the end, if you’re staying focused on making sure you’re providing a reason for all these elements (the companions only like certain weapons or can only logically use certain weapons – like teeth, it’s a more personal journey, you don’t become a priest because there’s a chance you were once a god yourself), no one really cares. And as long as you’re doing one thing really well (I’d argue in Torment’s case, that was the story and some of the game mechanic convention-breakers), that helps you stand out and carve out a game identity all its own.

In Numenera, Kevin Saunders (Project Lead) and Colin McComb (Lead Designer) are conscious of the original Torment’s shortcomings and its strengths, and combat and adventure are not downplayed in any of the design documents and discussions. I’ve also added my cautionary tales as well about player motivation and companion design, but Kevin and Colin already seem to grasp those points well, so it’s like preaching to the choir, really. Which is a good sign.

You've made a name with RPGs and dialogue trees. Do you ever want to try alternative narrative mechanics, or is this a path you're set on? If the latter, are further experiments like Alpha Protocol's dialogue system where you'd like to be, or are you content to further push the boundaries with the systems you have?

I think cinematic dialogue and menu-driven systems has put us in a dialogue cul-de-sac of diminishing returns on gameplay, and there’s more that can be done with dialogue systems, depending on the genre (Brian Mitsoda’s tension-driving, branching-but-linear-with-no-takebacks in Alpha Protocol I think very much complimented the espionage mechanics of the title).

Also, with our Aliens: Crucible dialogue system, we made a conscious effort to make sure the player could never take “refuge” in a talking head conversation – they should never feel safe, they should never feel like they couldn’t be attacked at any time in the environment... because, hey, that’s what Aliens is all about.

Usually the franchise ambiance or engine specs have been our guiding principles for dialogue system design, but there’s more room to grow. I’m really interested in helping develop the dialogue mechanics for Tides of Numenera, as the Numenera ruleset allows for some interesting speech–related applications that would work well in a new dialogue system.

You're working on the South Park RPG. How have you been involved, how is it working with Matt and Trey, and how were you affected by the publisher switch?

My involvement on South Park has been minimal, I worked on it for about 2-3 months helping assist with the cut scene pipeline, and that’s the extent of my efforts.

What games do you think have made interactive narrative a more interesting place to be over the last five years, and why? What blew you away, or expanded your horizons?

Walking Dead. I didn’t know if a largely narrative reactive title would work. It does. Now I know. BioShock: Infinite I thought took some brave narrative challenges (the context of Columbia and their moral compass in an otherwise beautiful world... and the fact it’s a beautiful dystopia is really interesting) in addition to the pre-existing strengths of the narrative design in previous titles (the big ones are visual storytelling, not letting the story get in the way of the player freedom to explore it).

And finally, since I've no doubt a bunch of my readers would like to know, what's the best way for someone to get a writing gig if you're hiring? Are technical level design skills a must, do you care about qualifications, which skills do you expect writers to bring to the table, and which do you think can be learned on the job?

That is (another) good question. So... technical design is helpful, but not required. So is programming, 3D art, animation knowledge, quality assurance training, web design... all of these additional skills beyond simply writing are helpful in game development, but not mandatory. That is not my way of saying you shouldn’t investigate and learn about supplemental careers, as all of these things make you a better narrative designer and a better developer.

The answer on how to approach being a narrative designer is a really long one, so let me try and highlight the big ones:

- Be accommodating. Your job is to support systems, not dictate them.

- Be helpful. Narrative is a powerful tool to explain away what would otherwise be considered a game’s limitations and problems. Make everyone’s life easier by volunteering ways to do this.

- Scriptwriting is a better focus for your time than novel or short story samples. Those are good skills to have, but scriptwriting (especially with regards to VO-centric titles) is more important.

- Graphic novels, imo, aren’t bad either. They teach how to use background visuals and camera and character placement to set up a scene, which is a good skill for a narrative designer to cultivate (and your storyboard artists and cinematic designers will hopefully appreciate this as well).

- Whenever possible, a narrative designer looking to get a leg up in the industry should shamelessly find a way to help Chris Avellone contribute to FTL2 because that would make Chris Avellone happy. If any narrative designer can do this, then the aforementioned Chris Avellone would be happy to help their narrative career however he can. Just saying, Tom, just saying.

- Narrative designers should look for ways to tell the story through visuals first, words second. Graffiti, prop placement, and vista-conscious level design are often more effective than listening to a talking head or a handler give a 3 minute exposition of what’s ahead.

- Story is not the most important thing unless you’re doing a Walking Dead/Telltale game. Don’t be stubborn, demanding, and insist that games are there to tell stories. You’re there to let the player have a cool experience, let them have it. Let them “mess up” your story. Let them do a non-ideal path if they want... and make it equally ideal, even if it isn’t the path you took. Your job is to entertain. Respect your audience and respect the fact you are making a game first, and your story supports that experience.

- Every time you interview for a writing gig, they will ask (or should be asking) about a story you liked or a story you hated or a story you felt indifferent about in a game. Then they will (should) ask you why. It helps if you have specific answers in advance. Keep a living post-mortem on your computer with critiques of the story of each game you play, and be prepared to speak intelligently about these story critiques in an interview at the drop of a hat.

I have one more bit of Chris-related news to share with everyone when the time is right. Stay tuned.